Distracted driving: how texting, eating and phoning at the wheel affects us

Think you can safely send a quick text while driving? Think again. We see how distractions really affect driving

Lack of concentration and failing to pay attention remain the biggest contributing factors in road accidents in the UK, with thousands of drivers and pedestrians killed or seriously injured as a result.

That’s not helped by the growing number of distractions fitted to modern vehicles, whether it’s increasingly advanced infotainment systems or the latest smartphones offering everything from sat-nav functions to hands-free calls.

Factor in those who continue to flout tougher laws on using a mobile phone to call or text, and it’s little wonder there are so many incidents caused by not concentrating.

We previously investigated what people got up to on the morning commute in to compile a list of the most common traffic offences. Unsurprisingly, mobile phone use topped the survey, whether that was making a call or looking at maps, while eating and drinking polled highly, too.

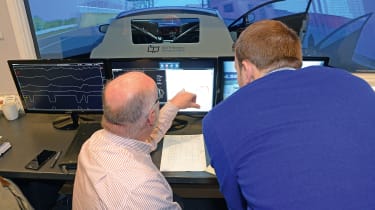

While all of these will harm your ability to focus properly behind the wheel, which is the worst? And how much impact do they really have? To find out, we teamed up with Base Performance Simulators in Banbury, Oxfordshire, to gather data to be analysed by biometrics and road safety experts to assess just how damaging making a call, sending a text or eating and drinking can be to driving.

• Record number of drivers caught using phones

We also drafted in the help of former British GT4 champion and current Formula 3 contender Jamie Chadwick to see how distractions can impact even a professional driver.

Alongside Jamie, we set benchmark laps in the simulator – set up for a Honda Civic Type R – around the short Silverstone National circuit with its combination of high and low-speed corners, straights and heavy braking zones. At the end of the final lap, we were instructed to brake at the start/finish line to judge our reaction speed.

This was repeated for each distraction, and Tim Shallcross from IAM RoadSmart analysed the difference in driving style for each, the resultant lap time and change in braking distance. We were both also fitted with a bio-harness to monitor our heart rate, respiration rate, core temperature and posture.

• What is a Driver Emotion Test?

This BioCOM system is used by pro athletes to ensure they’re operating at peak physical performance. Lower blood pressure and calm breathing can directly translate to smoother, better driving, while an erratic heart rate and over-exertion would eventually result in loss of focus. These biometric results would be analysed by fitness analyst John Camilleri. So how did we fare?

The tests and results

| Clean run | Joe Finnerty | Jamie Chadwick |

| Time | 01:12.5 | 01:08.5 |

| Braking distance | 115m | 105.6m |

We paired up with Base Performance Simulators in Banbury, Oxfordshire, to see how our performance would vary. We started the test with a clean run of the Silverstone National circuit to see how we’d compare.

Texting

| Texting | Joe Finnerty | Jamie Chadwick |

| Time | 1:44.165 (+31.710s) | 1:10.303 (+1.799s) |

| Braking distance | 97m (-18m) | 120.6m (+15m) |

What happened: We were tasked with composing a short pre-agreed text message, which led to us giving the most erratic lap of the test, with low speeds and lack of control. Jamie used the tactic of only texting on the straight, but it still returned her second slowest lap.

Analysis: The biometrics revealed Jamie hit peak heart and breathing rate during this test, so concentration levels were challenged the most. Shallcross said: “Joe would have been a menace to other road users; the car was more or less out of control. Jamie’s strategy reduced the distraction in critical zones, but a sudden incident would have left her unable to take avoiding action.”

Making a call

| Making a call | Joe Finnerty | Jamie Chadwick |

| Time | 1:16.088 (+3.633s) | 1:09.003 (+0.499s) |

| Braking distance | 130m (+15m) | 83.6m (-22m) |

What happened: The test started with us receiving a call from Shallcross during the lap. He asked questions that’d require us to think and it resulted in both our lap times being the third worse. Braking distance was middle of the pack, too.

• Six points and £200 fine for mobile phone use while driving

Analysis: Our biometrics showed Jamie to have a higher core temperature when taking a call, suggesting increased physical demand. Our test was done holding the phone, too, but Shallcross explained even hands-free calls are a distraction. He explained: “Phone conversations continue to distract when the driver needs to pay attention. Even Jamie’s racing-driver concentration was disrupted.”

Using a sat-nav

| Using a sat-nav | Joe Finnerty | Jamie Chadwick |

| Time | 1:15.852 (+3.397s) | 1:12.018 (+3.514s) |

| Braking distance | 131m (+16m) | 184.6m (+79m) |

What happened: For this test, we were given a predetermined post code – not familiar to either of us – to enter into our smartphones that were mounted on the windscreen. We had to open the app, enter the post code and activate route guidance. It resulted in the slowest lap time for Jamie by nearly two seconds, plus she missed the braking point altogether.

Analysis: Biometrics revealed this to be the most challenging for our body, with a peak heart rate 8bpm higher than other distractions. Breathing peaked, too, as we found it physically difficult to switch focus between driving and typing. Shallcross explained: “Both drivers were getting used to the distractions by now, but there was still a significant speed reduction for Joe, and the ultra-focused Jamie completely missed the stop line. The moral? Those warning screens about not entering details on the move are there for a reason – don’t ignore them.”

Talking to a passenger

| Talking to a passenger | Joe Finnerty | Jamie Chadwick |

| Time | 1:12.263 (-0.192s) | 1:08.456 (-0.048s) |

| Braking distance | 136m (+21m) | 134.6m (+29m) |

What happened: For this test, Shallcross jumped in the passenger seat of the simulator and conducted a similar conversation to the one we’d had on the phone. This time, the results were remarkably different, with both of us clocking our fastest lap times as we warmed up to the simulator and were devoid of any physical distraction. Interestingly, braking remained one of the worst results.

Analysis: Again, Jamie’s biometrics showed talking to the passenger increased core temperature just as the phone call had, but it didn’t have the same impact. Shallcross explained: “It was the least distracting of all in terms of lap times, but interestingly, both drivers failed to brake accurately at the target line. Their ability to drive normally confirms the difference between the extra distraction of a phone conversation and the natural act of talking to a passenger, but still shows that any distraction reduces attention, and in an emergency, it might be critical.”

Eating

| Eating | Joe Finnerty | Jamie Chadwick |

| Time | 1:16.975 (+4.520s) | 1:08.884 (+0.380s) |

| Braking distance | 141m (+26m) | 126.6m (+21m) |

What happened: This was the first of the distractions that isn’t an offence in itself, although it can be included as part of a ‘driving without due care and attention’ conviction. While it’s technically legal to eat behind the wheel, our study showed it was the second most distracting for us in terms of lap time – mainly because we struggled with the unwrapping of the energy bar.

Analysis: Shallcross said that our experience was exactly the problem that snacking poses, with the opening of the packet being the biggest obstacle to safe driving. He added: “After that, apart from the physical distraction of holding the food bar, they found it easy to cope. In the real world, ideally have a snack when parked, but if that’s impossible, at least open the sandwich container or food wrapper while stationary to minimise physical and mental distraction.”

Drinking

| Drinking | Joe Finnerty | Jamie Chadwick |

| Time | 1:14.893 (+2.438s) | 1:08.576 (+0.072s) |

| Braking distance | 127m (+12m) | 128.6m (+23m) |

What happened: As long as it’s not alcoholic, then drinking is legal on British roads, and plenty of motorists have a sip of water when driving on the motorway without any problem. Certainly it proved the least distracting activity for us and Jamie.

Analysis: Shallcross remarked that both drivers chose a straight to take a drink, minimising physical distractions, but said just like eating, the opening of a drink in the real world was crucial to avoid problems. He said: “It’s important to break the cap seal while stationary; doing it on the move is a mental distraction, as well as a risk of spilling the contents over your lap.”

Conclusion

Fitness expert Camilleri said the biometrics showed physical output for both us and Jamie was higher when presented with a distraction, compared with the benchmark lap. While Jamie’s biometrics were much more stable due to her expertise and wealth of experience in the simulator, ours were more erratic.

Camilleri added: “The amateur driver’s breathing rate was more erratic and there was considerable breath holding for the distraction variables that he found particularly challenging.”

But which was worst? We’ve crunched the numbers – combining, weighting and averaging our results for lap times and braking distances – to rank which is the most distracting task at the wheel.

Worse for braking (i.e. single critical situation on the road): Using a sat-navWorse for lap time (i.e. longer-term concentration): Texting

Distraction league table

- 1. Using a sat-nav

- 2. Texting

- 3. Talking to a passenger

- 4. Eating

- 5. Phone call

- 6. Drinking

What do you think of our results? Let us know in the comments section below...

Find a car with the experts