Cars: Accelerating the Modern World: visiting the V&A’s new car exhibition

Victoria & Albert Museum’s new car exhibition looks at the impact the car has had on the world

No invention has had more impact on the modern world than the car, which makes it worthy of celebration – or at least close assessment. That’s the thinking behind a bold new exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. Titled ‘Cars: Accelerating the Modern World’ and running from now until April, it’s an enjoyable, thought-provoking show.

“The car is the most important design object of the 20th Century in that it’s effected so much change,” says exhibition co-curator Brendan Cormier. “But sometimes you’re too close to something to have a proper look. This exhibition steps back for an objective glance at the car.”

• Exploring the Grampian Transport Museum

The show is arranged thematically rather than chronologically, and one of the first exhibits is the jet-powered 1953 Firebird concept car from General Motors. Interestingly, Cormier says, its successor, Firebird II, was a prototype self-driving car, imagined decades before today’s race to autonomy was envisaged.

“One of the leitmotifs of the show is that a lot of the things that seem incredibly contemporary we’ve actually been talking about for a long time. There has always been this dream of fluid mobility, for example; we’ve always been trying to get to the idea of streamlined shapes, and highways where there’s no traffic.”

Another idea that seems modern but is as old as the hills is personalisation. It’s easy to think of contrasting body colours as being a relatively new phenomenon, but eye-catching customer-specified paints were originally a response to the dominance of the Ford Model T.

“Manufacturers asked how they could compete with Ford,’’ Cormier explains. “You’ll never get a car cheaper, so in the 1920s Duco paints come out. And while the Model T is black because it’s the fastest-drying colour, other manufacturers realised they could use the car as an extension of people’s personalities.”

The Impact the Model T – and car production as a whole – has had on the world is a big theme of the exhibition, with one hall dedicated to how the world had to change in order to produce the car itself.

“Henry Ford’s project was one of total design. The new factories that needed to be built to accommodate the scale of production, the work he put in to supply cheap rubber to his company with Fordlandia [a failed project to build a city in the rubber-rich rainforest of Brazil].”

The complex relationship between man and machine is exemplified by the Tatra 77, which was developed by Austrian engineer Paul Jaray. “He cut his teeth on Zeppelin airship design,” Cormier says. “He comes up with the Zeppelin shape through wind tunnel testing, but decides to quit and devote himself to the automotive industry and sell the idea of streamlined cars. Tatra is the first one to work with him directly, and [the 77] is the result.”

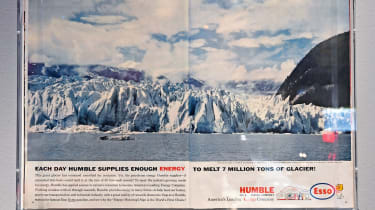

Both Cormier and the exhibition are full of ideas, and neither dodges car-related environmental concerns.

“We have the system we have today because we were sold a dream, a very provocative enticing dream that satisfies the individual,” he says. “The way out of the mess that we have at the minute is to come up with an equally compelling dream to sell to people. You can’t really do it on moral or ethical grounds.”

One of the last sections of the exhibition includes a looped film of three environments impacted by the car: oil fields in California; a Japanese highway system; and the lithium flats of the Atacama Desert, where vital minerals for electric car batteries are extracted.

Cormier explains the thinking behind this section. “It’s important to remind people that all of these things have consequences, and the last room is about how the car shapes the space around us. EVs seem clean, but involve another form of extraction. And it’s the billion-car problem. If you have a billion of any kind of technology, it’s going to have an impact, and here it’s playing out in the Atacama.”

The exhibition does not, Cormier says, offer a magic-bullet solution to the issues inherent in private car ownership; instead, it celebrates and examines the car and the world that has sprung up around it, giving visitors the chance to look back in close detail, and in broader context.

“It’s about looking in the rear-view mirror to see what’s next,” he says. “It’s important to have a nuanced understanding of how we have got to this situation in the first place. If you’re simply railing on it for the most visible issues, that cars are bad and cause climate change, that’s not a sophisticated enough stance to understand the answers.”

We came to the V&A expecting to see gleaming machines from across the ages. And, while you will find that here, you’ll also find an important exhibition that asks difficult questions, perhaps the largest of which is this: did we design the car, or has it ended up designing us?

Second opinion: what does a young visitor think?

“AT the start of the exhibition there were some funky-looking concept cars, but these were just guesses of what the future could have been like – the reality has been very different. And at the end of the show is an autonomous concept Audi with a set of propeller wings that plug onto the top to make it fly. As good as it may sound, it looks strange.

“My favourite exhibit was Graham (above), who looks like a caveman but is actually a model of what human beings might look like if they had evolved naturally to survive car crashes. His face is flat to absorb the impact, his head has extra fluids inside to protect his brain, and his chest is cushioned to absorb impacts.”

David Coquet, 12, Peterborough

Cars: Accelerating the Modern World, runs to 19 April. Adult tickets are £18, family tickets from £33, under 12s go free.

Find a car with the experts