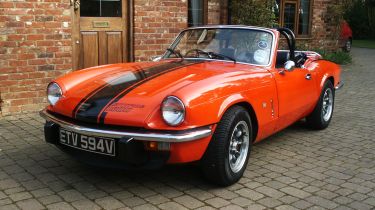

Triumph Spitfire: Buying guide and review (1962-1980)

A full buyer's guide for the Triumph Spitfire (1962-1980) including specs, common problems and model history...

The Triumph Spitfire was launched in 1962, and aimed to compete with the Austin-Healey Sprite, but in the same year another rival also surfaced – the MGB. Thanks to its separate-chassis construction, Triumph’s Herald provided the perfect platform from which to develop a new two-seater open-topped sportscar, even if the mechanicals were derived from the 1953 Standard Eight.

The Triumph doesn’t have a huge amount of power on offer, but with just 670kg to haul along, performance is better than you might think – especially as the 1147cc four-pot was fitted with twin carbs, a spicier camshaft and a more free-breathing exhaust manifold.

Which Triumph Spitfire to buy?

During nearly two decades of production the engine grew, the bodywork was restyled and the suspension honed to make the car’s handling more predictable. However, none of these cars are really fast and none will ever provide the élan of an Elan, but then you’re not paying Lotus prices either.

There are plenty of project Spitfires about, but if you want to restore the car properly, even at home, you’ll be doing well to break even if you buy something that needs a complete overhaul. However, you’re better off buying one of these or a really good car - rather than something in the middle. There’s a good chance that you’ll pay over the odds for a car that needs plenty of work.

Used - available now

2018 Nissan

Qashqai

32,700 milesManualPetrol1.3L

Cash £12,800

2021 Mercedes

A-Class

41,000 milesAutomaticPetrol1.3L

Cash £17,300

2020 BMW

X2

46,200 milesAutomaticPetrol2.0L

Cash £17,200

2016 Audi

S3 Sportback

54,700 milesAutomaticPetrol2.0L

Cash £17,000There’s not much difference in values between the various Spitfire incarnations; the later cars are more usable but the earlier ones offer greater design purity. As a result, they’re all equally sought after – although the Mk3 is a particular favourite as it has nicer lines than the MkIV and 1500 yet it’s relatively usable.

There were three different engines fitted throughout the life of the Spitfire, with each one also fitted to other models in the Triumph range. Because the Spitfire was generally the most highly tuned of the lot, you need to make sure the engine fitted is the one that belongs there, as less powerful units are often substituted from other Triumph models.

All Spitfire engine numbers start with an F: FC in the case of the MkI/MkII, FD for the MkIII, FH for the MkIV (but FK for US cars) and FH for the 1500 (FM for US cars). However, there’s a good chance that something else will be fitted, such as an engine starting G (Herald), D (Dolomite) or Y (1500 saloon).

MkI and MkII Spitfires were fitted with an 1147cc engine, but because these early cars are rare, you’re unlikely to find a car with one of these rather gutless powerplants. Even if you do find a first or second-generation car, the chances are the engine will have been swapped for a later unit by now. The MkIII featured a 1296cc powerplant, which was carried over to the MkIV, but with less power because of emissions control equipment.

The first three generations of Spitfire featured the same four-speed manual gearbox, with synchromesh on all gears except first. The MkIV was fitted with the same transmission, but with synchromesh on all ratios, while the 1500 received a Marina-derived unit, which is the most durable of all the gearboxes.

Triumph Spitfire performance and specs

| Model | Triumph Spitfire 1500 |

| Engine | 1493cc, in-line four-cylinder OHV |

| Power | 71bhp @ 5500rpm |

| Torque | 82lb ft @ 3000rpm |

| Top speed | 101mph |

| 0-60mph | 12.9secs |

| Fuel consumption | 29.8mpg |

| Gearbox | Four-speed manual (optional overdrive) |

| Dimensions and weight | |

| Wheelbase | 2108mm |

| Length | 3683mm |

| Width | 1448mm |

| Height | 1207mm |

| Kerb weight | 712 kg |

Triumph Spitfire common problems

• Engines: the 1147cc and 1296cc engines are very durable, but all Spitfire engines must have the correct oil filter fitted if they’re not to expire prematurely. This filter features a non-return valve to stop the oil draining back into the sump when the car is left; if there’s much rattling when the car is started up, it’s because the crankshaft’s big-end bearings have had it, probably because the correct type of filter hasn’t been fitted. Once this has happened, a bottom-end rebuild is necessary.

• Small engines: these two smaller engines will usually clock up 100,000 miles without problems, with the first sign of wear usually being a chattering top end because of erosion of the rocker shaft and rockers. Budget for a top end rebuild.

• Thrust washers: a problem that affects the 1296cc engine all too often is worn thrust washers, given away by excessive fore-aft movement of the crankshaft. The easiest way to check this is to push and pull on the front pulley; any detectable movement means possible disaster as the crankshaft and block could ultimately be wrecked. MkIV Spitfires are especially prone to these problems; listen for rumbling from the bottom end as the engine ticks over.

• Crankshaft wear: the 1493cc engine fitted to the Spitfire 1500 has problems of its own, as the crankshaft can wear badly, along with the pistons and rings. Listen out for rattling and blue smoke.

• Gearbox: all of the gearboxes are reasonably long-lived, but big mileages will lead to rebuilds being necessary.

• Synchro: synchromesh is usually the first thing to go, so check if there’s any baulking as you go up and down the gears. Also listen for whining, indicating that the gears have worn, or rumbling, which signifies the bearings are on their way out.

• Overdrive: many Spitfires have overdrive, which can also give problems. The first thing to check in the event of non-engagement is that the electrics are working okay; they’re often the main cause of problems. If not, the oil level has probably fallen below the minimum. The worst case scenario is a rebuilt overdrive for around £250.

• Propshaft: if the propshaft needs balancing, there’ll be a vibration at a certain road speed, which disappears once you accelerate. Worn universal joints are given away by clonks as the drive is taken up when moving off in forward or reverse.

• Clutch: clutches don’t give any particular problems, so just check for slipping as you accelerate, or juddering as you let the clutch out.

• Differential: the differential will whine when it’s worn. Even when things sound really bad the rear axle will just keep going, but it’s obviously something to sort.

• Suspension: thanks to the flip-up bonnet, the Spitfire’s front suspension is simplicity itself to work on. That’s just as well because there are various bits that can give trouble – but it’s all very cheap and beautifully simple to put right.

• Bushes: the nylon bushes in the brass trunnions can wear, so feel for play with a crowbar. The main problem with the trunnions is wear of the threaded brass at the bottom, if EP90 oil hasn’t been pumped in every six months or so.

• Rubber bushes: there are various other rubber bushes throughout the suspension, all of which will perish at some point – but they’re cheap to buy if somewhat involved to replace if you want to fit a complete new set

• Anti-roll bar: the anti-roll bar links can also break, but at just £8 each that’s nothing to worry about. The same goes for the rest of the front suspension; there are all sorts of potential weak spots but they’re all quickly and cheaply fixed.

• Bearings: the wheelbearings can wear, as can the track rods end, steering rack and upper ball joints that locate the top wishbone. The rubber steering rack mounts can also perish, usually after they’ve been marinaded in leaked engine oil. Your best bet is to feel for play by getting underneath.

• Suspension: the rear suspension can also give problems, but it’s generally easy to overhaul, with one key exception; the wheel bearings. These wear out and are a pain to remove as a press is needed.

• Springs and dampers: the only other likely problem, apart from worn or leaking shock absorbers, which are easy to replace, is a sagging leaf spring. If the top of the wheel has disappeared above the wheelarch, the spring needs to be renewed.

• Steering: the rack-and-pinion steering is unlikely to have any problems, as it isn’t under much strain, despite the Spitfire’s fabulously tight turning circle.

• Brakes: it’s a similar story for the brakes; they’re completely conventional so you just need to be on the lookout for leaking rear wheel cylinder, sticking caliper pistons and seized handbrakes. All parts are available.

• Rust: corrosion is the Spitfire’s main enemy; it can strike in the bodyshell as well as the chassis, and the sills are essential to the car’s strength.

• Home repairs: many owners restore their Spitfires at home and don’t brace the bodyshell when the three-piece sills are replaced, twisting the bodyshell.

• Sills: start by looking at the integrity of the sills; the area where they meet the rear wings is where corrosion is the most likely, and once rot takes a hold, long-lasting repairs will require skill.

• Water in the sills: also take a look at the leading edge of each sill; there’s a good chance of holes here. Water will get in, wreaking havoc throughout the sill.

• Rot: there are plenty more rot spots to inspect too: the rear quarter panels, door bottoms, boot floor and the windscreen frame can all corrode badly.

• More rot: so too can the A-posts, wheelarches (inner and outer) plus the headlamp surrounds and front valance.

• Yet more rust: floorpans also corrode, sometimes because rot spreads from the sills and sometimes because the footwells have been allowed to fill up with water.

• Panel gaps: next check the door shuts, which should be even all the way down. If a car has been badly restored, with the shell twisted in the process, the door won’t be flush all the way down and neither will the shut lines be even.

• Crash damage: accident damage is also a strong possibility, as these cars often appeal to inexperienced drivers after some cheap fun. If the car has been in a major shunt, the damage will be obvious; any prang big enough to distort the main chassis will have wrecked the car’s delicate panels.

• Chassis damage: it’s the small knocks that are likely to cause you the most problems, as they may be harder to spot. However, if the panel fit is all over the place at the front, there’s a good chance the front chassis rail, to which the valance attaches, has been knocked out of true.

• Electronics: although there’s a good chance that some sort of electrical problem will be present, it’s usually only down to poor earths or the failure of some cheap-to-replace component. Everything is available and there isn’t anything that’s a problem to fit.

• Trim: similarly, the trim shouldn’t pose any problems as most of it is being remanufactured. Some bits for early cars are tricky to get hold of however, but if you’re looking at a MkIV or 1500, you can re-trim the car to original spec or upgrade it easily and relatively cheaply.

Triumph Spitfire model history

1962: Spitfire breaks cover, with 1147cc engine.

1965: MkII edition goes on sale, with more power and a stronger clutch.

1967: The MkIII arrives, with a 1296cc engine, a hood that’s much easier to use and revised styling.

1970: The MkIV bring another facelift, plus an all-synchromesh gearbox and more predictable handling thanks to revised rear suspension.

1971: Seatbelts now fitted as standard.

1973: A 1500 edition makes its entrance, for the US market only. The bigger motor is needed because of all the emissions control equipment that has to be fitted. There’s also a wider rare track, to overcome handling issues.

1974: Spitfire 1500 on sale in the UK.

1977: The interior receives minor fettling for greater comfort.

1980: The final Spitfire is made.

Triumph Spitfire summary and prices

Thrills don’t come much cheaper than with one of these; even less costly than an equivalent MG Midget or B, the Spitfire is perhaps the cheapest way of enjoying topless motoring. For not a lot of cash, you can buy a Spitfire that’ll keep going; if you’re handy with a socket set you could even pick up a project for just £1000.

You’re going to struggle to find anything that offers the same amount of fun as the Spitfire, if you’re on a seriously tight budget, but such low values are a double-edged sword because there’s a lot of rubbish available as a result. That’s okay if you buy a project car knowing it needs a lot of work.

Most cars have been restored by now and originality is hard to find; suspension systems, exhausts, engines and wheels are often upgraded so don’t expect to find a time-warp car. A lack of originality isn’t generally an issue (although it may be to you), but poor restorations are a problem because many home restorers cut their teeth on cars like the Spitfire.

The good news though is that it’s easy to spot a duffer from 100 paces, so buy with your eyes open and get set for some cheap fun. Early cars are certainly the most valuable, with Mk1, Mk2 and Mk3 models all commanding up to around £8000 in top condition.

Average cars sell for £3000-£5000, with projects starting from around £1000. Later Mk4 and 1500 models are still the bargain models, maxxing out at around £5500, with decent runners on the market for £2000-£3750. Viable projects can still be found for around £850.

Thinking of buying a future classic? Then take a look at these future classic cars